The Challenge of Perennials

The more I grow perennials – and the more I take on the challenge of trying to grow them from seed – the more I appreciate how intricate are their survival mechanisms for ensuring germination.

Annuals are easy. Squashes, lettuce, marigolds: they all want to sprout. They want to consume as many nutrients as are available, grow as fast as they can, get pollinated, make seeds, and die. It’s an intense, one-shot deal.

Perennials, though, take their time. They grow more slowly. Their roots dive deep. It’s more about relationships, timing, endurance. We must try to

I started this post with the simple idea of sharing a list I’ve been gathering on seeds that require stratification, i.e., a period of cold, before they will germinate. Actually, this term might be a bit misleading. More accurately, we are giving the seed a conditioning period, i.e., getting them into a condition in which they can germinate.

As it turns out, perennial seeds have a wide assortment of inhibitors and requirements that can delay germination. For example, some seeds have incredibly hard coats that require multiple cycles of freezing and thawing before they will crack enough to allow moisture to penetrate and swell the seed hidden within. Some require chemical digestion by birds. Some require light; others darkness. Essentially, these are all survival mechanisms to ensure the new seedlings have the best chances possible for success.

How Do We Know Which Needs What?

We need to think like a plant. A plant is rooted where it is. It might be able to expand its territory through its roots, but it can transport itself over long distances through its seeds. How can it optimize its chances for success? Can it get past winter cold, summer heat, scorching fire, flood, or intestinal indigestion? All potential challenges, even for me.

Once we understand where the plant is coming from, we can try to recreate those conditions. Does it come from the high desert? Tropical jungles? Alpine meadows? Deep forests? Mediterranean coastlines? Next, the elements and processes: Does the seed fly with the wind? Does it simply drop down, be covered with leaves, and wait for snow melts? Do hormones activate awakening? Bacteria in the soil? Possibly a combination of factors?

Despite all my attempts at channeling my inner seed, I cannot tell you how many flats I have given up on and dumped in a bed or around a tree, hoping that they still might make it and maybe I would eventually recognize their little sprouts amongst the tall weeds.

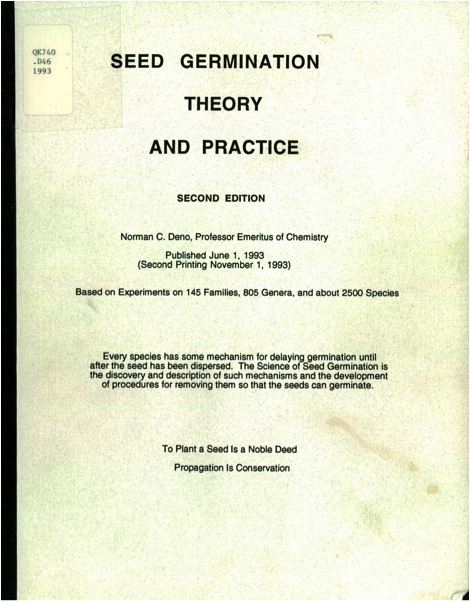

Enter: Norman C. Deno – Seed Germination Theory and Practice

In my quest to better understand how to increase my germination success, I came across Norman C. Deno’s work on “Seed Germination Theory and Practice,” published in 1993, currently out of print but online at the link. Norman Deno (1921 – 2017) served as Professor Emeritus of Chemistry at Penn State University and conducted germination experiments on over 2500 species of plants, in 805 genera, and from 145 plant families – no small task! On the cover of his book, he notes:

“Every species has some mechanism for delaying germination until after the seed has been dispersed. The Science of Seed Germination is the discovery and description of such mechanisms and the development of procedures for removing them so that the seeds can germinate.”

Here are some key points from his work:

- An important distinction: it is not that a seed is “dormant,” but rather that seeds have different mechanisms for blocking germination until conditions are right. Every plant has one or more mechanisms for delaying germination.

- Don’t assume that just because a plant is in the same family that it will have the same “delay mechanism.”

- Most seeds have at least two delay mechanisms, one of which Dr. Deno calls a “chemical time clock.” Different conditions will trigger the alarm to go off that tells the plant to wake up. Once met, another goes off that sets another chemical process in motion to begin germination, and so on.

- By the same token, many seeds have a two-step (or more) process where the “Don’t Germinate” mechanism has to be destroyed before the “OK, GO!” mechanism can be started. We used to think this was accomplished by storing at 40 degrees and then shifting to 70 degrees F. However, tests have shown the reverse can also be true. Some species have several delay mechanisms that must be destroyed in a specific sequence and within certain temperature and time constraints before germination can begin.

- Some species germinate best when temperature and conditions oscillate.

- About half of plants from temperate areas need not only

soaking, but also a drying period. Did we all think that plants just need warm, moist conditions to sprout? Think again. Of course, too much drying can also kill the sprout. - Seeds from desert areas typically germinate at cooler temps (35-40 degrees F). It makes sense. They typically have to get a quick start in early spring when there might be water.

- Seeds in fruits often have to be separated from the flesh, which can contain chemical inhibitors. Birds and mammals often assist this process through their digestive enzymes. Inhibitors might also be washed away through repeated rinsing with water in the form of rains or melting snows.

- Some seeds cannot germinate in the dark. They need UV light. This is common of swamp area plants where water is plentiful but

light is a limiting resource. As we all know, this is also true for many weed seeds. They remain dormant buried in the soil, but when we till or otherwise bring them to the surface where they can see the light, they sprout all over the place. - Some plants produce a hormone, gibberellin, that aids in germination. By soaking the seeds in a solution of Gibberellic Acid-3 (GA-3), we can break down inhibitors and accelerate the germination process. GA-3 was identified by Japanese scientists studying diseases in rice back in the 30s. It is now commercially extracted from the fungus, Giberella

fujiuroi , and you can actually buy it online right here. Dr. Deno did a lot of experimentation with GA-3. He cautions that it does not work on all seeds, and on some, might even inhibit germination. It has been shown to strengthen disease resistance and increasesize and yield of fruit. Or it might kill the plant. A little goes a long way. Too little is ineffective; too much is, well, too much. Ho w a seed is stored will have a huge influence on its viability. Most seeds prefer dry cool conditions; however, they can also get too dried out. Many others last much longer in moist conditions.- Dr. Deno used two main temperatures in his experiments: 40 degrees F and 70 degrees F (i.e., cool and warm). According to Dr. Deno, seldom were other temperatures needed.

At this point, you, like me, might be ready to throw up your hands and declare, “It’s all too complicated!” I would like to think that Dr. Deno has provided us with a blueprint. Unfortunately, to make matters more confusing, I find conflicting recommendations across the Internet (which should surprise no one). For example, starting with the letter A for Angelica. Almost all Internet sources (including reputable nurseries) say it requires cold stratification. Dr. Deno, however, says it needs 70L, meaning 70 degrees with

Whether we are adding hormones, trying to create a sense of winter, replicating spring rains, or otherwise messing with seed to make it think we are the real deal, we are trying to mimic the natural processes that encourage a seed to come to Life. If we get it right, assuming it is viable seed, they will respond.

Cold Stratification

[su_row][su_column size=”1/2″]We return to what, initially, was to be the beginning of this

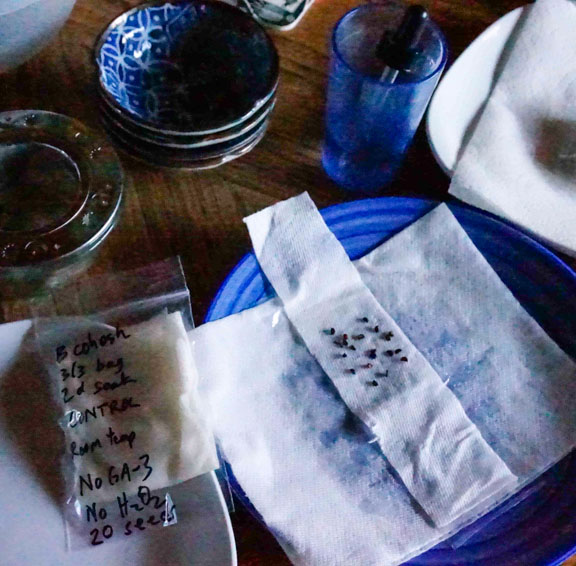

How to Cold-Stratify Seeds: Simple Guidelines for the Baggie-in-the-Fridge Method

The basic method is to put a wet paper towel or some damp planting medium in a baggie, add seeds, label it, and put it in the fridge for a month or longer. Simple, right? Remove and plant any seeds that have sprouted. Continue with cold, if specified, or switch to warmth (and possibly exposure to light). Again, check progress, remove and plant sprouts. Some may need a return to the fridge. Some may need to repeat this cycle, maybe even for a couple of years. Good luck with that.

Every species is different, so it’s good to look up what information might be available, and for that I recommend Tom Clothier Horticulture and Ontario Rock Garden and Hardy Plant Society databases. You might also search Norman Deno’s work.

Don’t have time for all that research? That’s ok.

A few basic rules:

- Nick, lightly sand, or gently file the shell of large seeds (called scarification)

- Soak large and medium-sized seeds

- Large and medium-sized seeds can go in plant medium or be wrapped in a damp (but not soaked) towel. Personally, I prefer just placing the seeds on top of the towel so I can see them through the baggie.

- Place small seeds on top of a moistened paper towel where you can keep an eye on them.

- Most seed packets will give a recommended time for chilling. Label your baggies, include date to pull them out, organize them by pull-out date, and stick them in the fridge.

Options that * Might * Increase Success

Water Additives for Soaking Seeds (may also be added to paper towel or planting medium):

Liquid Kelp: Sometimes I add a little liquid kelp to the seed soaking water. I keep it very dilute.

Hydrogen Peroxide: It is claimed that hydrogen peroxide stimulates many species to germinate and is recommended in Dr. Deno’s instructions as something to experiment with. You might try adding a tablespoon to a cup of water. I tried using H2O2 a few years ago but my results were inconclusive due to many confounding factors I won’t go into here. I am going to try again.

Willow Water:The scientific literature on this is mixed, and may even indicate that willows contain seed germination inhibitors. Willows contain various “auxins” that act as rooting hormones, but how soluble they are in water is debated. Some people make a tincture with the willow in alcohol, but then the alcohol could be harmful to plants if it is not removed first (heat the liquid and the alcohol will evaporate off before the water boils). Willows also contain salicins, which convert to salicylic acid, the precursor to aspirin. Salicylic acid can help in the defense against fungi, viruses, and bacteria. I have lots of willows and make willow water every year from shoots in early spring. I mix it with liquid seaweed and use it in rooting cuttings and fertilizing new starts. I haven’t tried it with soaking seeds, though.

Liquid Smoke and Charred Wood: Yes, if you add Liquid Smoke to water or soak a piece of charred firewood in water, the seed might react as a fire survivor, and some seeds need that.

GA-3 Solution: Look up individual species in Dr. Deno’s document to see if GA-3 is recommended (or give it a go on your own). Dilute GA-3 powder in a few drops of alcohol at first to make it more soluble. Add water to recommended dilution ratios. Either soak seeds in solution or apply to paper towel for small seeds. You can also use Dr. Deno’s direct method of placing an amount that fits on the end of a round toothpick on a damp paper towel. I used GA-3 several years ago with some success. I am going to try it again this year with better control of all the variables.

Remember: Seeds need oxygen. They need to breath. Open the bag now and then to check them. Don’t drown them. You want a damp paper towel – not a soaking wet one in the baggie. There should not be a lot of water that runs into the corners of the bag.

Potting Mixes: I feel potting mixes can be useful because you don’t have to prick a fragile seed sprout out of a paper towel; you can just plant them. A sterile seedling mix can be handy for large seeds. Some people use straight vermiculite because it holds the moisture, and the seed doesn’t need nutrients until after it gets going; plus, it is easily rinsed off when transferring to a pot. Some people prefer peat (for acidic pH plants); others abhor peat and go with cocoa coir. Some prefer very fine sand for the smaller seeds because it facilitates even spreading out. Go with what works for you.

Advantages of Baggie Method

Whatever medium you use, the advantage of the baggie method is that they will not get lost in the weeds. Planting in pots after cold conditioning is a controlled option, but for me, plants in pots often get dried out, overly soaked and spindly, susceptible to damping off, or scavenged by critters.

Yes. It would have been so much easier to just sow them outside last fall. Had I done that, I wouldn’t be writing this. I wouldn’t have gone down this dark, cold rabbit hole of information on cold stratification and seed germination requirements, hormones, enzymes, potting mixes, additives, and secret codes interspersed between temperature and time.

Final Perspectives

I go outside. I look at the plants with a slightly different perspective. How does the next generation get a good start? Which plants commonly self-sow? They are probably the ones that like a little winter or need light to germinate. Which ones seem to appear out of nowhere? Those probably have a hard seed coat that requires pre-digestion – and maybe were lucky to be dispersed by voles or birds and happened to fall upon a soil type where they can thrive. Maybe brought by the wind? Some might even germinate several years down the road after they have long been forgotten – maybe they just need more time and help from nearby bacteria and fungi.

The point is – seeds can wait and they often do.

We impatient gardeners, not so much.

Seeds will teach us patience – or make us deviously creative in our attempts to jumpstart this miracle called life, where a root suddenly emerges to reach downward and a leaf stretches toward the sky.

How to fool a tiny seed into thinking the time is right? Think like a seed. Let Nature do the work when you can, but if you missed that window, try to be an effective imposter. Experiment. Seeds have much to teach us, do they not?

Thanks for reading,

~ * ~

References & Additional Info

Deno, Norman C. 1993. “Seed Germination Theory and Practice.” https://naldc.nal.usda.gov/download/41278/PDF U.S. Department of Agriculture, Beltsville, MD.

DuQuette, Edward. “Farming with an Old Technology that Copies Nature’s Basic Formula.” Cornell Small Farms Program. https://smallfarms.cornell.edu/2015/07/06/farming-old-technology/

Gibberellic Acid: How it Works and Where to Buy it. http://www.jlhudsonseeds.net/GibberellicAcid.htm

Ontario Rock Garden & Hardy Plant Society website: Seed Germination Guide

Pavlis, Robert. “Germinating Seeds with GA3.” Onrockgarden.com http://www.onrockgarden.com/sites/default/files/ORGS%20Germinating%20seeds%20with%20GA3.pdf

Pavlis, Robert. 2018. “GA3 – Gibberellic Acid Speeds up Seed Germination. Garden Fundamentals. http://www.gardenfundamentals.com/ga3-gibberellic-acid-speeds-up-seed-germination/

Penn State Extension, College of Agricultural Sciences, Seed and Seedling Biology: https://extension.psu.edu/seed-and-seedling-biology

Prairie Moon Nursery Seed-Starting Tutorial https://www.prairiemoon.com/PDF/Prairie-Moon-Nursery-Seed-Starting-Basics.pdf

Tom Clothier Horticulture Site – amazing resource! https://tomclothier.hort.net

Wojtyla, L., K. Lechowska, et al. 2016. “Different Modes of Hydrogen Peroxide Action During Seed Germination.” Frontiers in Plant Science 7:66.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4740362/ [/su_column]

[su_column size=”1/2″]

Seeds that Like Cold Stratification

(L) denotes seeds that require light to germinate.| Seed, Common Name | Scientific Name |

|---|---|

| Agrimony | Agrimonia eupatoria |

| Anise Hyssop (L) | Agastache foeniculum |

| Arnica (L) | Arnica chamissonis |

| Artichokes | Cynara scolymus |

| Astragalus | Astragalus membranceas |

| Autumn Olive | Elaeagnus umbellata |

| Bachelor buttons | Centaurea cyanus |

| Balloon Flower | Platycodon grandiflorum |

| Berberis | Berberis spp. |

| Bergamot / Beebalm (L) | Monarda spp. |

| Betony | Stachys officinalis |

| Bilberry | Vaccinium myrtillus |

| Black Cohosh | Actaea racemosa |

| Bloodroot | Sanguinaria canadensis |

| Blue Bean Tree | Decaisnea fargesii |

| Blue Cohosh | Caulophyllum thalictroides |

| Blue Vervain | Vebena hastata |

| Boneset (L) | Eupatorium perfoliatum |

| Burnet | Sanguisorba minor |

| Butterfly Weed (L) | Asclepias tuberosa |

| Calamus | Acorus calamus, A. americanus |

| Camas | Camassia quamash |

| Catmint | Nepeta mussinii |

| Catnip (L) | Nepeta cataria |

| Ceanothus / Red Root | Ceanothus spp. |

| Chamomile (L) | Anthemis nobilis |

| Chinese Blackberry Lily | Belamcanda chinensis |

| Chinese Lantern | Physalis alkekengi |

| Chives / Garlic Chives | Allium schoenoprasum, A. tuberosum |

| Cilantro | Coriandrum sativum |

| Cleavers | Galium aparine |

| Columbine | Aquilegia vulgaris; A. canadensis |

| Echinacea | Echinacea spp. |

| Elderberry | Sambucus spp. |

| Elderberry | Sambus nigra, S. canadensis |

| Eryngium | Eryngium planum |

| False Indigo, Blue | Baptisia australis |

| Gentian (L) | Gentiana spp. |

| Geranium, Wild | Geranium maculatum |

| Ginseng | Panax spp. |

| Goji | Lycium barbarum |

| Goldenrod (L) | Solidago spp. |

| Goldenseal | Hydrastis canadensis |

| Good King Henry | Chenopodium Bonus-Henricus |

| Goumi | Elaeagnus multiflora |

| Hawthorn | Crataegus spp. |

| Heather | Eupatorium cannabinum |

| Hemp agrimony (L) | Eupatorium cannabinum |

| Hollyhocks | Alcea rosea |

| Hops | Humulus lupulus |

| Joe Pye Weed | Eupatorium maculatum - L |

| Jujube, Chinese date; Spiny Jujube | Ziziphus jujuba, var. spinosa |

| Juniper | Juniperus spp. |

| Lady's Mantle (L) | Alchemilla vulgaris |

| Larkspur / Delphinium | Delphinium spp. |

| Lavender (L) | Lavandula angustifolia |

| Lemon Balm (L) | Melissa officinalis |

| Licorice | Glycyrrhiza glabra, G. uralensis |

| Linden | Tiila cordata |

| Lobelia | Lobelia inflata |

| Lomatium | Lomatium dissectum |

| Lupine | Lupinus spp |

| Marshmallow | Althaea officinalis |

| Meadowsweets | Filipendula ulmaria |

| Medlar | Mespilus germanica |

| Milkweed / Pleurisy (L) | Aslepias syriaca |

| Motherwort | Leonurus cardiaca |

| Mountain Mint (L) | Pycnanthemum virginianum |

| Mugwort | Artemisia vulgaris |

| Mulberries | Morus spp. |

| Mullein | Verbascum thapsus |

| Oregano (L) | Origanum vulgare |

| Oregon Grape | Mahonia spp. |

| Osage Orange | Maclura pomifera |

| Passionflower | Passiflora incarnata |

| Penstemon | Penstemon harwegii |

| Perennial Sunflowers | Helianthus |

| Phlox | Phlox |

| Plantain | Platago rugelii |

| Primrose | Oenothera speciosa |

| Quamash, Camass | Camassia quamash |

| Quince | Cydonia oblonga |

| Ramps | Allium tricoccum |

| Rhodiola, Rose-root (L) | Rhodiola rosea |

| Rose | Rosaspp. |

| Rosemary (L) | Salvia rosmarinus |

| Rudbeckia | Rudbeckia fulgida |

| Sage | Salvia officinalis, Salvia spp |

| Saint John's Wort | Hypericum perforatum |

| Scabiosa | Scabiosa spp. |

| Schisandra | Schisandra chinensis |

| Sea Kale | Crambe maritime |

| Seaberry | Hippophae rhamnoides |

| Sedums | Sedum spp. |

| Self Heal | Prunella vulgaris |

| Skullcap | Scutallaria lateriflora |

| Soapwort (L) | Saponaria ocymoides; S. officinalis |

| Solomon's Seal | Polygonatum biflorum |

| Spikenard | Aralia racemosa |

| Stinging Nettles (L) | Urtica dioica |

| Sweet Cicely | Myrrhis odorata |

| Thyme | Thymus vulgaris |

| Trillium | Trillium spp. |

| Valerian | Valeriana officinalis |

| Vervain | Verbena officinalis |

| Violet (L) | Viola spp. |

| Wild Ginger | Asarum canadense |

| Wild Rose | Rosa spp. |

| Wild Strawberry | Fragaria spp. |

| Wild Yam | Dioscorea villosa |

| Wintergreen | Gaultheria procumbens |

| Witch Hazel | Hamamelis virginiana |

| Wormwood (L) | Artemisia absinthium |

Mother Nature and her trickery. Stratification is not an area into which I have purposely ventured or have read much about.

The detailed info you have provided is fascinating. It also explains my current struggle with germinating my Verbena bonariensis..”Be sure to do your research!” 🙂 Like you, I’m taking on the challenge of trying to broaden my capability to grow from seed. A big THANK YOU for taking time to write such a comprehensive article!

Thank YOU, Karen! I have gone from shaking my head at all the wasted seeds & pots & thinking, “Why do I even bother?” – to – with a better understanding of where the seed is coming from and what it does to better survive, greeting long awaited sprouts. Very satisfying experience! (except when they later get nipped off by roly poly pillbugs! but that’s for another story). Good luck to you!

P.S. Tom Clothier says for Verbena bonariensis, “Sow at -4 to +4ºC (24-39ºF) for 4 wks, move to 20ºC (68ºF)for germination.”

Best laid plans,I know the feeling! Then there’s the flip side when something wonderful comes up you didn’t give thoughtful time and care. If only I wasn’t so OCD. …Happy Spring to you.

Haha! I can SO relate! Happy Spring to you, too, and thanks for stopping in!