[Link back to Site Analysis; Link back to Permaculture Journey]

Hydrology and Water Sources

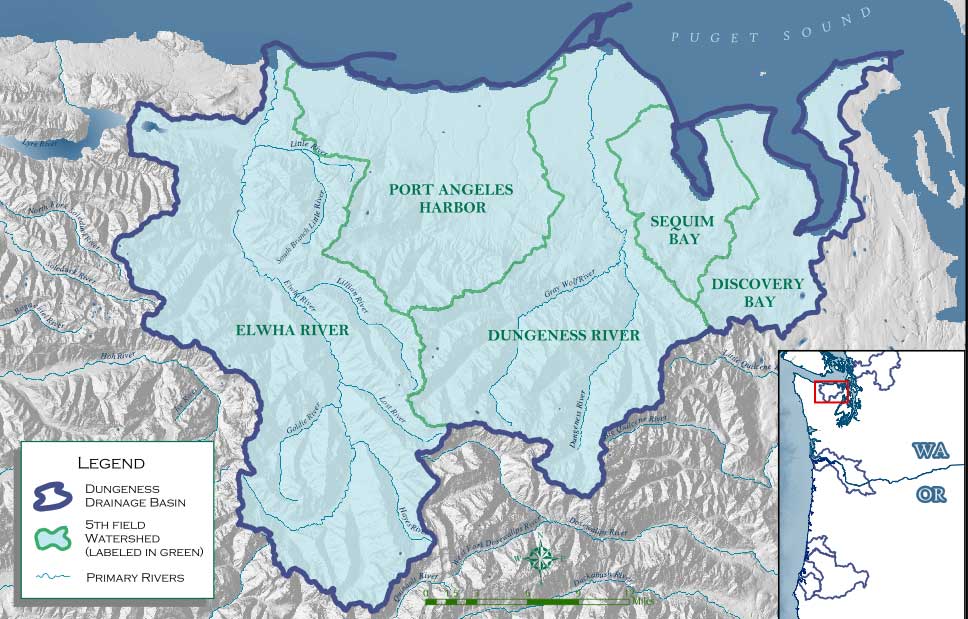

The Dungeness River Watershed

An understanding of hydrology and of the surrounding watershed is helpful in better understanding the water issues confronting the Barbolian Fields homestead and many other home sites and farms in the region. The Dungeness Watershed comprises approximately 200 square miles. The Dungeness River itself originates in the Olympic Mountains and cascades 35 miles steeply downhill (the 7800-foot drop makes it one of the steepest rivers in the United States) through wilderness, forests, agricultural land of the Sequim Valley, and out into Dungeness Bay, which is a designated wildlife reserve. The watershed is home to over 200 fish and wildlife species and is an important stopover point for migrating geese and other waterfowl. Nine salmonid species are known to dwell in the river; the renowned Dungeness crab is named for the Dungeness Bay, which also hosts numerous fish and shellfish species.

In 1896, early pioneers dug a phenomenal network of irrigation ditches to bring water from the Dungeness River to the semi-desert of the Sequim-Dungeness Prairie. Their vision of “Water is Wealth” enabled this area to become predominantly agriculture. The Barbolian Fields site is fortunate to have water rights grandfathered in on one of these irrigation ditches, which borders the east side of the property. It is the main source of water for the gardens. Because of the limited rainfall, the region primarily depends on deep wells, snowpack reserves in the Olympics, and this network of irrigation ditches, which is now an extensive 300-mile irrigation system providing water to over 25,000 acres.

The watershed is carved by a series of glaciated ice sheets into multiple ravines, which channels water flow until it reaches the plateau of the Sequim Prairie. In the lowlands, it is further channeled by a series of dikes and weirs (some of which are now being removed to restore traditional tidelands and waterways), and, as noted above, diverted through the irrigation ditch network. It is estimated that the regional aquifer has dropped 10 feet in the last 10 years. The aquifer is relatively shallow (approximately 100 feet) and is closely connected to levels of the Dungeness River, which are monitored routinely.

Water Availability:

One would think that a location close to the mountains and within the Dungeness River watershed would have no problem with water. Quite the contrary. Water use, quantity, and quality in this region have become increasingly controversial topics. Population explosion, septic failures, a change from largely agricultural to more urban uses, vegetation removal, developmental impacts, stormwater runoff, and assorted nonpoint source pollutants have degraded water quality, resulting in salmonid population declines, shellfish closures, and fecal coliform counts in groundwater.

Although agriculture land use has declined, and only about half of what used to be drawn from the ditches is currently being used for farming, a tremendous increase in population (which doubled between 1970-1980 and jumped another 50% in the last 10 years), along with an increased number of wells and a corresponding increase in the use of water, has definitely had an impact on regional water supplies. However, according to hydrologists, recent efforts to pipe the ditches to reduce maintenance costs, evaporation, and surface contamination, is resulting in a much greater reduction in the amount of water that formerly recharged the aquifer. The result: wells are going dry. Permaculture techniques to capture and conserve water will become essential in the years ahead.

Water Resources at Barbolian Fields:

At Barbolian Fields, the primary source of household water is from a well approximately 90-feet deep. The water quality is excellent and rich with minerals. However, in late September, when the region experiences severe drought, the well tends to suck a bit of sand and other particulates.

The main source of irrigation water is from the irrigation ditch that borders the eastern edge of the property. However, is it dependable? Recent controversies over the ditches, increased water demand, and the threat of future regulation of water use make over-reliance on this system ill-advised. The ditches, which divert water from the Dungeness River, “run” from April 15 to September 15, after which time they are shut down to leave water in the river for salmon runs. Unfortunately, this coincides with our driest time of year, a time when water is most needed in gardens.

Conservation Practices:

In 2009, the owners at Barbolian Fields purchased two 250-gallon rainwater catchment tanks and positioned them to capture the runoff from the metal barn roof. It quickly became apparent that when it rains, there is such an abundance of water, the tanks quickly overflow. However, when it is dry, the two tanks cannot even come close to providing enough water for the garden. The following are ideas incorporated into the permaculture plan for the Barbolian Fields site that will help to even out these cycles of flood and drought:

- Rainwater catchment and overflow diversion from every roof surface into holding tanks, ponds, rain gardens, and sunken areas for water-loving plants.

- Installation of a drip irrigation system that more directly distributes water to established perennials and specific planting areas.

- The use of swales, pits, raised beds, and berms to further concentrate (and in some cases, direct) water flows. A creative use of these techniques will be required as the land is relatively flat.

- Construction of hugel beds to further conserve water.

- Implementation of other water conservation practices, such as timing of watering, use of mulch pits and sunken compost tea buckets to fertilize surrounding plants, etc.

- Creation of microclimates through planting of additional trees and shrubs to increase condensation, decrease evaporation, and moderate temperatures.

- The use of mulch to decrease evaporation, build soil microbial communities, and increase carbon material in the soil, which will absorb and hold more water.

- Additional plantings of native plants that are better able to conserve water, are adapted to this climate, and that provide food and shelter for birds and wildlife.

- Plantings of more perennials, which have deeper root systems and are better at weathering seasonal flood-drought swings; plantings of fewer annuals.

- Creation of a windbreak along the western side to reduce water loss due to strong winds.

- Creation of microclimates to support plants that are more “needy” but still desirable.

- Strategic placement of rocks to increase condensation and provide housing for small animals.

- Channeling of household greywater to the west end of the property, where there will be a pond and future home site for ducks. Plants to filter the water will be grown along the channel edges.

- Increase in personal conservation practices; reduction of consumption and waste.

Resources and References:

Dungeness River Audubon Center website

Dungeness River Targeted Watershed Initiative, Final Report to the Environmental Protection Agency prepared by the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe in December 2009

Dungeness Water Watch Newsletter produced by the Local Leaders Water Management Work Group and Ecology

Pacific Coast Watershed Partnership

Permaculture: A Designers’ Manual by Bill Mollison

Sequim-Dungeness Hydrogeology by Davy Nazy, Department of Ecology

WA435 – Relation Between the Dungeness River and the Shallow Aquifer in the Sequim-Dungeness Area, Clallam County, Washington – Completed FY2002