Today is the last day of winter. Tomorrow we cross that vernal equinox demarcation into Official Spring. Yay! The mornings are still very frosty, and several heaps of stubborn piles of snow remain in the shadows of the roofline where, to keep our roof from collapsing, we pulled off what seemed like small mountains of heavy white stuff. We are SO ready for spring! But Wait! Before we leave winter behind, this is a perfect time for a winter garden site assessment (roll eyes here). But hear me out. The winter garden can offer surprising insights. So grab your beverage of choice and let’s take a little garden tour. I promise you it will be useful.

Winter allows us to see the bare bones of the garden.

Without the frills of leaves and underbrush, we can see the framework that holds it all together. Sure, a lot of it looks like a complete disaster – a flattened mat of bent-over stems, grasses, and assorted weeds. Ignore all that for the moment and step back. What we are looking for is the skeleton that gives the property structure, which is so much easier to see when the greenery doesn’t fill in all the spaces.

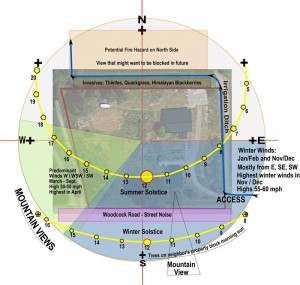

I like the permaculture approach to a site assessment as it starts out with the basics: Sun, wind, water, patterns. By revisiting these parameters, we can also see how the garden has evolved and how conditions have changed. We can identify what works (or not) and get ideas for future enhancements. The winter garden bares the essence of what is there.

First Observations. What do we see?

- Topography: This seems so obvious, but from a bird’s eye view, we want to see if we are making the most of what we have, whether it be contoured slopes or (as in our garden) relatively flat terrain. However, even flat land is not completely flat. Gullies, swales, ditches, raised beds, mounds, hills… whatever we have – are we using it to best advantage?

- Basic Infrastructure: buildings, pathways, ingress and egress, utility areas

- Water Sources: city water, well, other irrigation sources, waterlines, ponds, and streams

- Primary Vegetation: location of trees and shrubs; open fields; orchards; garden beds; potential microclimates

- Zones: Main areas that are most used (Zones 1-3): family gathering areas, garden plots, orchards, animal housing and yards – to – areas of the least use (Zones 4 & 5), i.e., areas seldom visited or left to be what they are. It is more efficient, for example, to have intensively managed garden beds close to the house. Chickens can be a bit further away, but still need to be convenient for feeding and egg collection. Wildlife habitat is on the outskirts.

Identifying Sectors and “Energy systems” – Sun, Water, Wind, Soil

Solar Sector:

As the vernal equinox approaches, we are inspired to follow the sun. Where are the shadows – or lack of shadows? Notice how the movement of the sun changes from a narrow arc in winter to a wide arc in summer, daily shifting from low to higher in the sky. Where did the snow linger longer; which areas dry out first; what receives the most winter sun; and what is likely to get scorched in the summer heat?

And also, how do we capture the sun — whether high-tech panels or a pile of rocks, in water features, in vegetation, a south-facing wall, or reflected off pavement – we can modify our design and plant choices to make the most of what is available. Frost will settle in low-lying areas; bricks and rockery will absorb the heat of the day and continue to radiate warmth after the sun goes down.

By the same token, how do we provide shade? Are deciduous plants located to provide summer shade / winter sun? How can we create microclimates to best suit our needs?

Water Sources:

What are our sources of water? Understanding where the water comes from and where it flows to (in our case, from the mountain watershed to the sea), how to divert it in plentiful times and store it for lean times, how to manage, conserve, and when possible, reuse whatever we have: these are becoming ever-more important topics.

We don’t have to be hydrologists to understand rainfall and snowpack trends and how they affect our immediate aquifers. We do need to figure out how to best manage what is available to us.

We use two 250-gallon rainwater catchment tanks to catch the rain from the metal roof of our barn; we divert the overflow to a couple of small ponds, and the overflow from those into the soil. When the rain falls, we can’t possibly catch and store it all in the tanks. The problem is that they are full when we least need it, and during the drought months, it is never enough. However, when we lost power over the winter, they sure came in handy. They also get a lot of use just before the irrigation water is turned on in mid-April and after it is cut off in September. Redundant systems give security. Last year, I put a lot of effort into upgrading to a drip irrigation system that is connected to our (now piped and under pressure) irrigation ditch. There is still much to do to complete a fully integrated system. The walk-about is a good time to figure out the next steps.

Other water conservation techniques, such as using lots of mulch, building wicking beds, Olla clay-pot systems, and plant variety selection, to name a few, can help provide and conserve water. I have long used raised beds for my garden areas. I am starting to re-think that. Perhaps I should be planting in mulched pits? Other options – swales, rain gardens, additional routing from rainwater collection systems, and things I can do to either modify the microclimate (more trees and perennials!) or improve the soil to conserve more water, are all good strategies. Of course, not everyone has the sprawling garden I have created – which may be something I need to condense. The winter garden site assessment is a good time to figure out how to reel it in a bit.

Wind:

The wind routinely blows through here at 35 mph and sometimes harder from off the Pacific Coast. Other times it flips and comes in from the east. Or it will blast us from the north. Where is the best place for windbreaks? Which plants are best able to withstand strong winds? (Hint: NOT sunflowers and corn!) How might you provide protection to vulnerable areas in the garden?

And to turn the problem into the solution: what practical means do we have of capturing the wind energy? We’ve been told we don’t get enough wind to justify the cost of a turbine, but I really question that assessment!

Resilience in the Face of Disasters:

For those living in the path of hit-or-miss hurricanes, an analysis of the wind sector must seem a bit silly. There are some elements over which we have no immediate control and perhaps can only be lessened through moderating climate extremes – not an immediate solution. Resilience in the face of disaster, whether by wind, fire, or flood, is a topic beyond this post, but definitely worth seriously thinking about. How might the homestead withstand extreme events? Would there be food? Fuel? Shelter? Medicine? Could you take care of the animals? Communications? After our extended power outages and heavy snows this last winter, being prepared is no longer just for “preppers.”

Soils:

Soil can also be thought of as an energy source; after all, this is the source of a plant’s energy, which is then transferred to us. How do we build our soils? What mulch material do we have available? How efficient are our compost systems (answer for me: room for improvement!). Do we have worm bins? Barrels for compost tea? Green manure crops? Sources of wood chips? Soils rich in humus are better at storing water, and many say water is best stored in the ground. There are lots of things we can do to continually improve our soils.

Patterns:

While examining all these elements, identify overall patterns: wind, sun, water flow, the rhythms of seasons, and the way in which the various wildlife respond to and follow them. Again, it’s not only recognizing the patterns, but also our relationship to them – how we might, for example, place spring and fall-flowering plants near the beehives, create habitat along the edges, plant spring greens in areas that get the early spring rains but also some summer shade, plant several rows of shrubs to make hedgerow buffers against the winds, take advantage of the early morning sun or escape the late afternoon heat.

Examine the Edges

When I walk around the garden, I often skirt the edges. The edges are where the action is, where you find the most diversity and the most growth. The edge of one habitat is always trying to intrude on the other, and visa versa. There are not distinct lines from deep forest to open meadow, but along the transition zone is where you will find a lot of wildlife. These areas seem to have the most resilient plants: those able to survive – even thrive – under diverse conditions. It is often a good area for foraging.

When I do a winter garden site assessment, I am looking for these transitional areas, connections, and interactions. What has evolved or changed? Some plants are larger; others are crowded out. Where is the landscape on the natural succession timeline?

Wherever I go, I try to see what pieces don’t seem to fit – and also which do.

Narrow the View from Large Scale to Detail

It is easy to get sidetracked in the details (aha! Another bird’s nest!), but in trying to keep with the concept of defining the garden skeleton, I look to see how details fit in – or where there might be a hole in the landscape where something could be created. Also, where are the most interesting spots located? Hidden away or out in the open? Are they practical, for example, an herb spiral by an outdoor cooking area? In winter, we are more confined; it can be important to have something of interest in the window view, for example, a bird feeder or plants that stand out in a wintry landscape.

The winter garden tends to emphasize the focal points. Benches, sculptures, centerpieces, lines and textures…. As in a painting, what draws the eye? Where are you called to go to? A circle surrounded by herbs and flowers? To an unusual piece of art? A path to a hideaway? The berry patch? Are the paths a direct shot to the destination – or do they lead you somewhere that encourages you to go a bit farther? Are there places to just stop and listen?

To-Do List vs Opportunity List:

Sometimes in the walk-around, all we can see is the mess. I carry a notebook and write my to-do list, which quickly becomes overwhelming. Pruning, cleaning, dividing, moving… these are always a part of late winter / early spring. It’s always amazing to me how much random trash resurfaces after winter.

More importantly, though, I write down ideas, inspirations, and opportunities. I look for quick things I can do that give a lot of immediate effect for the least effort (always a morale booster). When the ground is too wet to dig, for example, it is a good time to focus on pathways – and sometimes that simple definition is enough to make everything else stand out. (Plus, I find that if the pathways are well-defined, especially if there are stepping stones, children love to follow them and skip from one to the next. The berries disappear just as fast, though, with or without pathways.)

I look for fun things to do:

- New focal points and creative expressions – perhaps a water feature, living wall, or troll haven?

- Places for trellises, beds, circle guilds, a new willow sculpture? A new garden hideaway?

I also try to

- Identify connections – how one enhancement can help many more

- Increase efficiencies – maybe a new keyhole bed near the house for salad greens?

- Reduce and simplify – always hard for me, but easier to make decisions when summer growth is out of the way

- Optimize by filling in – because if a desired plant isn’t growing there, a “weed” most certainly will if it can, right?

- Identify needed changes – wrong plant, wrong place vs right plant, right place. As the garden evolves, sometimes these mistakes are more obvious.

- Optimize plant communities / guilds – could a group of plants use an insectary partner? Is there room for a vine? Groundcovers? Could drought-tolerant plants be planted around the edges?

- Make the most of a plant’s features – for example, where might we use evergreen shrubs to create a cozy, protected enclosure, and where might we plant deciduous trees, shrubs, and vines to provide summer shade and also let in the winter light.

Aligning with Goals

The winter garden site assessment is a good time to reexamine our goals. Is the garden growing in the right direction? Perhaps we want to create a bird and bee sanctuary; grow mostly natives; emphasize food production; grow our own herbal medicines; make a safe place for kids, pets, and other animals; build something beautiful with a high wow factor; or simply create a low-maintenance, low-stress, comfort oasis.

Whatever your goals, the garden tour can help you identify problem areas and make difficult decisions about what is possible now, later, or maybe a nice idea but not a priority after all.

Need More Ideas?

When you’re all done, get some outside-the-planter-box perspective and inspiration. For me, a walk to the river showcases the framework of nature’s winter garden. Nurseries, seed swaps, and plant sales, on the other hand, not so much. These places are filled with hope and optimism and are crowded with people with vision. What is it about spring and gardeners, anyway? (I am kidding, of course! Hit these places up!)

I return to my garden. It no longer looks cold and naked to me. I marvel at that first little dandelion, the precursor to an entire field of yellow and fluff; those first shoots of lovage, smelling so strongly of celery; and the first leaves of nettles that are such a deep, rich, mineral-filled color. Extraordinary! I spot a couple of hummingbirds who have somehow survived the winter snows and are now flitting about together in search of insects, nectar, and a protected spot for nest building. The bees are out now on every sunny afternoon, their saddlebags filled with light yellow pollen.

We are all definitely ready for spring – but before we jump in, it’s a good opportunity for one final look around. Examine the basic structure. See what stands out. What needs propping up and what can be extended. Look at what has evolved and how that affects the surroundings. What are the outside influences. What is efficient; what can be better optimized.

Look now while you can, because tomorrow, spring is going to explode all over the place.

What a wonderful website/blog! I just discovered it today whilst hunting for something else (that I found on Pinterest) and have tucked you away in my RSS Feed Reader so that I won’t miss any more of your truly excellent posts. I live in Northern Tasmania, not too far away from Steve Solomon, one of your finest exports who moved to Tasmania many years ago after owning and running the Oregon seed company for many years. Our conditions here in Tasmania are quite similar to yours and much of what I read here is pertinent to my own garden. I live on 4 acres out in the bush on the Tamar River near the top of Tasmania and am trying to create a food forest here much to the amusement of the local wildlife who are most appreciative of my efforts to the point of rendering most of my efforts extinct (sigh). Looking forward to engaging and learning from you into the future. Thank you for posting about your wonderful property and your lovely life 🙂

What a lovely comment! You seriously just made my day. People like YOU are why I go on writing. People like you remind me that we are all one on this planet, kindred spirits, trying to keep what is important in perspective, trying to make the world a better place. Thank you so much. I would love to hear more about where you live, what you grow, and all the critters around you who appreciate you and what you do. Best wishes.